In the first of our case studies produced by researchers working with the York Explore archives, Carmen Byrne focuses on Wood Street, a street of 1850s terraces demolished in the 1970s to make way for new social housing. Drawing on Health Inspection reports and records associated with Compulsory Purchase, Carmen reveals the opposition to the Council’s decision to demolish from the York Group for the Promotion of Planning and evokes the serious emotional impact of living in a house slated for demolition.

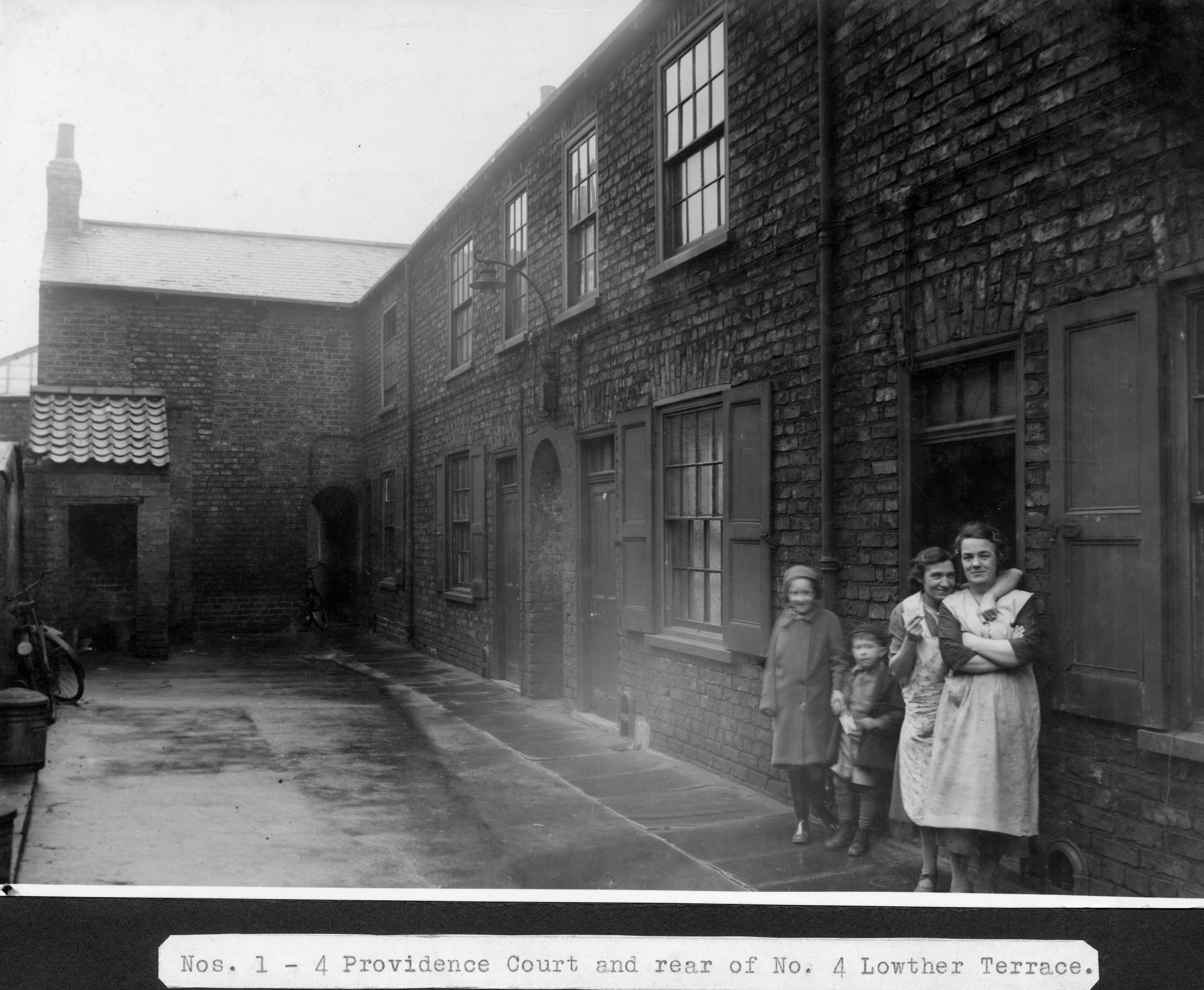

Having lived in a terrace house built in the mid19th century, albeit in the depths of Lancashire mill country, I was drawn to Wood Street, located at the heart of York, because of its familiarity. Built in the 1850’s the terraces on Wood Street were earmarked for compulsory demolition at the beginning of the 1970’s with housing inspection reports declaring them unfit for human habitation. Rising damp, uneven and worn floors, steep badly lit staircases and poor ventilation were regular features of the 1971 House Inspections: all sounding very similar to the little terrace I lived in only 5 years ago, where despite re plastering, insulating and some structural work, the damp appeared to be as much a part of the  building as the brickwork. Despite waging a never ending battle with the damp, this terrace was home for 10 years, so I can very much sympathise with the residents of Wood Street when they were informed their homes were at threat. It’s easy for us to look back from the warmth of our centrally heated houses and be slightly mortified at the lack of heating, warm water and bathrooms in some of the Wood Street properties, but it’s worth remembering that this was still pretty commonplace at this time. Although probably less common, was the bath tub fitted into the kitchen of 22 Wood Street: unfortunately there’s no photographs in the archives- just a slightly bemused note from the housing inspector!

building as the brickwork. Despite waging a never ending battle with the damp, this terrace was home for 10 years, so I can very much sympathise with the residents of Wood Street when they were informed their homes were at threat. It’s easy for us to look back from the warmth of our centrally heated houses and be slightly mortified at the lack of heating, warm water and bathrooms in some of the Wood Street properties, but it’s worth remembering that this was still pretty commonplace at this time. Although probably less common, was the bath tub fitted into the kitchen of 22 Wood Street: unfortunately there’s no photographs in the archives- just a slightly bemused note from the housing inspector!

With 43 houses and 59 occupants reported in 1972 as part of the compulsory purchase order, it was necessary for the Council to both purchase homes from owner/occupiers, as well as from private landlords (some of properties were vacant), as well as relocate tenants from social housing. It appears as though some of owner/ occupiers were also relocated with those tenants from social housing and private landlords. In all, there were a lot of people to keep informed, negotiate with and support with alternative arrangements as part of the street clearances.

With 43 houses and 59 occupants reported in 1972 as part of the compulsory purchase order, it was necessary for the Council to both purchase homes from owner/occupiers, as well as from private landlords (some of properties were vacant), as well as relocate tenants from social housing. It appears as though some of owner/ occupiers were also relocated with those tenants from social housing and private landlords. In all, there were a lot of people to keep informed, negotiate with and support with alternative arrangements as part of the street clearances.

The whole process from housing inspections in 1971 to the last relocation apparently in 1976 took 5 years. We can imagine the turmoil of residents especially when there appears to have been an element of distrust around the motives for demolition, rather than undertaking a refurbishment. The York Group for the Promotion of Planning voiced their concerns around the cost of a demolition project, when social housing was already at a shortage, with over 1300 on the waiting list and with “houses being allowed to decay and fall into disuse” (26th February 1974). Being “allowed” to fall into decay suggests a lack of care over a long period of time and as the York Group for the Promotion of  Planning stated this lack of care for small terraces was habitual across York, the condition of housing on Wood Street appears typical. There are a few ways to think about this: perhaps it was a reflection of a lack of refinement in managing social housing; perhaps firmer legislation was required to enforce private landlords to take better care of their properties; or maybe it was due to a longstanding social housing agenda to reshape York. Proof of Evidence for the Compulsory Purchase was given as “All the houses show rising and penetrating dampness in varying degrees, due to the inherent defects of the construction” which suggests no matter the care given to the properties, the fundamental issue is the construction itself which could explain the widespread state of small terraces across the city. Whatever the motivations, the process from inspection to relocation would have left property owners (the council included) in limbo, in that property maintenance would have possibly been perceived as a waste of money- triggering a downhill spiral over 5 years for properties which really needed care and attention much earlier.

Planning stated this lack of care for small terraces was habitual across York, the condition of housing on Wood Street appears typical. There are a few ways to think about this: perhaps it was a reflection of a lack of refinement in managing social housing; perhaps firmer legislation was required to enforce private landlords to take better care of their properties; or maybe it was due to a longstanding social housing agenda to reshape York. Proof of Evidence for the Compulsory Purchase was given as “All the houses show rising and penetrating dampness in varying degrees, due to the inherent defects of the construction” which suggests no matter the care given to the properties, the fundamental issue is the construction itself which could explain the widespread state of small terraces across the city. Whatever the motivations, the process from inspection to relocation would have left property owners (the council included) in limbo, in that property maintenance would have possibly been perceived as a waste of money- triggering a downhill spiral over 5 years for properties which really needed care and attention much earlier.

The emotional trauma of the residents of Wood Street and nearby Eastern Parade, who were also living in the same housing limbo for a number of years, can be seen in the archives through the letters written to the Housing Inspector. One tenant from Eastern Parade wrote to the Public Health Inspector in January 1973 requesting further information as she’d “held back a week’s holiday which must be taken before the end of the financial year”, so she was “naturally anxious to know if we are likely to move in the near future”. The resident’s uncertainty stemmed from having no news since she visited the Inspector’s office around one  year earlier and her concern about a series of “cleaning and replacement jobs which must be done if we are going to be here longer”. This would suggest that there was little transparency or communication with the residents during the process, and again reinforces the lack of ongoing investment into properties already resigned to demolition. It must have been frustrating, and in some cases very upsetting for residents: records of visit by a member of the council to a recently widowed owner/ occupier outlined “…it is hearsay, but acceptable, that his mental and physical condition was affected by four years of anxiety” in reference to the death of her husband.

year earlier and her concern about a series of “cleaning and replacement jobs which must be done if we are going to be here longer”. This would suggest that there was little transparency or communication with the residents during the process, and again reinforces the lack of ongoing investment into properties already resigned to demolition. It must have been frustrating, and in some cases very upsetting for residents: records of visit by a member of the council to a recently widowed owner/ occupier outlined “…it is hearsay, but acceptable, that his mental and physical condition was affected by four years of anxiety” in reference to the death of her husband.

Over 60 residents from the local area registered complaints for the demolition, and wider support came from the Yorkshire Evening Press. The local media reported that although some houses are unfit “especially after being empty for long periods of time” this doesn’t apply to all of them “The majority are structurally sound and have gardens which are large by present day housing standards” (Jan 9th 1974 Yorkshire Evening Press). So, we begin to see a  discrepancy between the framing of Wood Street on the Compulsory Purchase Order as being all unfit for human habitation and the perceptions of the general public (residents included). Examination of the compensations paid to the different property owners of Wood Street seems to reinforce the public and resident perception that not all houses on Wood Street were inhabitable. At a time when the average UK house price was £5,632 (not York or property specific) the highest compensation payment of £3500 is 62% of the market value compared to the lowest payment detailed in the archives of £175 at 3% of the average property value. This is a marked distinction which suggests varied house conditions. Owner/ occupiers also seemed to have looked after their homes more than private landlords renting them out, as the average owner/ occupier compensation was over £2,000.

discrepancy between the framing of Wood Street on the Compulsory Purchase Order as being all unfit for human habitation and the perceptions of the general public (residents included). Examination of the compensations paid to the different property owners of Wood Street seems to reinforce the public and resident perception that not all houses on Wood Street were inhabitable. At a time when the average UK house price was £5,632 (not York or property specific) the highest compensation payment of £3500 is 62% of the market value compared to the lowest payment detailed in the archives of £175 at 3% of the average property value. This is a marked distinction which suggests varied house conditions. Owner/ occupiers also seemed to have looked after their homes more than private landlords renting them out, as the average owner/ occupier compensation was over £2,000.

Broadly speaking there were a great deal of concerns about the loss of a community which had been established for over 100 years and indeed memories of Wood Street describe a thriving community. A member of the York Past and Present Society recalls how she “to play in the street as a kid in the 1960’s… there were three stables, Horwells’ coal, Rhodes fruit and veg, Leo Burrows Fruit and Veg…an old Cobblers shop and a mechanic had his workshop there too”. There was a mix of residents, from families to OAPs and we can also see a range of occupations from students to Rowntree process workers, bus drivers, security officers and home helps.  The green eyed monster can definitely rear its head when we think about how our communities today are often less defined by the streets we live in and more by our digital connections. Another reason for a nostalgic view of Wood Street in 1971 is the amount of rent paid in proportion to the average wage. Of the residents of Wood Street with listed occupations the average rent was £1.44 per week or £66.12 per year. In 1971 the average UK salary was £41.67 per week or £2000 per year which means a remarkable 3% of income would have gone towards rent. Putting this into a modern context of an average York wage £22,000 (in 2013) and with a small house (similar proportions to a mid-century terrace) renting in York for around £700 per month, rent can easily now be a massive 38% of our income!

The green eyed monster can definitely rear its head when we think about how our communities today are often less defined by the streets we live in and more by our digital connections. Another reason for a nostalgic view of Wood Street in 1971 is the amount of rent paid in proportion to the average wage. Of the residents of Wood Street with listed occupations the average rent was £1.44 per week or £66.12 per year. In 1971 the average UK salary was £41.67 per week or £2000 per year which means a remarkable 3% of income would have gone towards rent. Putting this into a modern context of an average York wage £22,000 (in 2013) and with a small house (similar proportions to a mid-century terrace) renting in York for around £700 per month, rent can easily now be a massive 38% of our income!

The Wood Street community was gradually dispersed between 12th February 1975 and 19th August 1976 based on the relocation dates found in the archives (there may be more tucked away). The owner/ occupier of 23 Wood Street had purchased the property in 1931 and was relocated to Hewley Avenue on 7th April 1976: moved 1.1 miles from a property which had been home, and residents which had been neighbours for 45 years. On average new homes seem to have been found within a 1 mile-ish radius of Wood Street, but in many cases the residents were located opposite directions- in essence 2 miles or so from their longstanding neighbours. A time of upheaval both for those leaving their community but also for those who were left behind in an emptying street. The Yorkshire Evening Post ran an article highlighting the trauma face by the 75 year old resident of 32 Wood Street living between two empty properties “My life’s a misery. They (“tramps”) climb over my wall, walk up the garden and have thrown bricks. I am very frightened” (6th January 1973). Although prior to the beginning of the relocation dates, the issues of empty properties and fragmented communities must have impacted on the happiness of those remaining, especially as more and more people moved.

In the early 1980’s new social housing was built on Wood Street, including flats. Today these still stand and appear to remain largely social housing, with only 2 recent property sales. A far cry from the 1970’s rent of £1.44 per week, a flat on Wood Street sold in 2003 for £82,500 with an estimated value of £147,000 in 2015. How times change.

Carmen Byrne. PhD Researcher, University of York.